Learn what “telling” is and when it’s actually better than showing.

If you have ever attended any creative writing class, or even just Googled “how to write,” you have likely seen the phrase “show, don’t tell.” I talk about it myself in a previous post that you can check out here: Show, Don't Tell—A Quick Overview. “Showing” is immersive; it means using the five senses and descriptive writing to help readers feel like they are in the middle of the action. “Telling,” on the other hand, uses exposition and summaries to convey information. Because we want our readers to be invested and immersed in our stories, it’s easy to see why “show, don’t tell” can be called the “Golden Rule” of good novel writing.

So, I hear you asking, why are you telling me (see what I did there?) to break this important rule of immersive writing? A good way to know how to use a rule is to know how to break it. And break it in the right ways at the right time. Telling does have its place in good novel writing. In fact, it’s an essential element. Read on to learn how to use telling to your advantage.

The Short Story

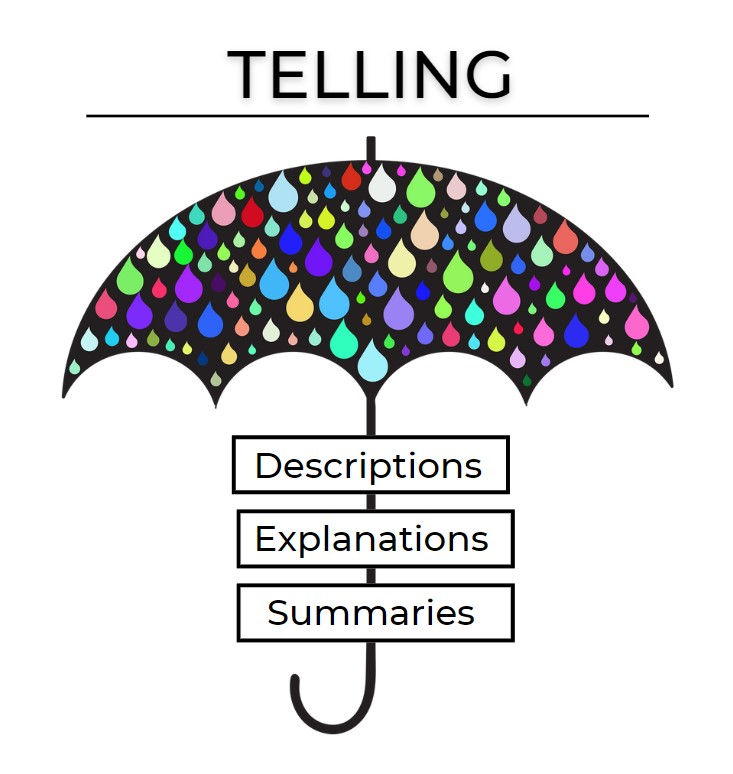

Explanations, summaries, and descriptions all fit under the “telling” umbrella and all are essential elements of novel writing. Telling is good in the following three areas:

To set the scene

To retell events

To create dramatic effect

The Novel

1. To set the scene

When you’re writing a passage with the purpose of giving information, telling can be a good way to go. These passages are often summaries, backstories, and descriptions of settings or worlds.

Often, if an author describes the nature of their unique world or setting, they will use telling. We don’t need to be shown all the details of the past 1,000 years of your civilization. However, if the information directly applies to a character, many authors incorporate showing. This rule is not hard and fast; it depends on your intent. Look at the following two examples:

Example 1: My family has raised horses ever since my grandpa stole a horse from a slaughterhouse sixty years ago. Our family motto has always been, “Ponies over profits.”

Telling works in this scene because of the author’s purpose: to set up why the speaker’s family raises horses and their intent behind doing so. Additional details are not shown because they are not needed to achieve this purpose.

Example 2: Nearly two hundred years ago, Jim Blanchard, my ancestor, stumbled through rows of animals, arms full of cigarettes he was supposed to be selling at the auction house. Instead, his nose and mouth filled with the scent of manure and animal sweat, and his eyes swirled as he took in the mass of animals and men.

Here, the author’s purpose is to show how the speaker’s grandpa felt and acted when he bought his first horse at an auction. This scene may be great in a story that talks about a boy’s relationship with his grandpa.

The bottom line: Use telling to give secondary information, brief backstories, and to move the reader from scene to scene. Use showing for scenes that deepen characterization or reveal significant plot points. Remember to keep your telling parts short and to the point.

2. To retell events

Telling keeps the current action as the focus by only giving us the facts we need to keep the story moving. Showing then draws us into the action, giving us visuals and play-by-plays. Tensions are high, as we the readers are witnesses to an unfolding sequence of events. When you use telling to quickly convey information the reader already knows (or doesn’t really need to know), you keep the story—and the tension—going.

Let’s imagine you have spent a chapter showing a character going through something intense, say, coming across a group of chanting teenagers at midnight in a graveyard who, upon seeing said character, began screaming and chasing him. If this scene is shown well, we will feel the tension of wondering who these people are, why they are in the graveyard, and what they will do to our character if they catch him. We’ve read every gritty detail. What we don’t want now is reading about that character meeting up with their friends and recounting the incident—gritty details and all—that we just read two pages ago. We know how the incident went, so the tension is gone and the retelling is almost always boring to the reader. Don’t stop the story to restate information the reader already knows.

Below is a good example of how an experience can be communicated without being retold.

Ex: Jack told his friends about the group of teens in the graveyard, the freakish way they chanted under the moon, and the loud screams they made when they saw him on his bike.

“How’d you get away?” Ben asked.

Jack shrugged. “I’m a fast rider.”

3. To create dramatic effect

Telling doesn’t allow for much nuance or interpretation from your readers—which is one of the biggest reasons why you will hear over and over to show and not tell. This is generally good advice. When you utilize showing well, and often, your readers will understand the vibe of the scene and how your characters are feeling. So, when you come out and tell how a character is feeling, readers will know you mean business. Telling can be a great tool to set up tension or ensure readers know how a character feels. Internal dialogue is where this kind of telling usually takes place.

Ex: She watched him walk away and hoped he never came back.

Ex: She wondered if the man had really told her the truth.

Ex: He prayed they could get to the car in time or all would be lost.

The Published Examples

“Mr. Bennet’s property consisted almost entirely in an estate of two thousand a year, which, unfortunately for his daughters was entailed in default of heirs male, on a distant relation . . .”

(Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: Penguin Books, 2020, p. 29.)

In this example, telling is used to establish a key aspect of the story: Mr. Bennet’s daughters are not able to inherit their father’s property. Thus, marrying well is of utmost importance. The background behind the actions taken by the Bennet family is now set.

“He lived a scant two years with his wife, and they had a son. At the divorce proceedings, the judge awarded the infant to its mother and ordered Tomas to pay a third of his salary for its support.”

(Kundera, Milan. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. London: Faber and Faber, 2014, p. 11.)

In this example, the reader is the audience receiving the recap. Tomas’s first marriage meant little to him; thus, he tells us the little we need to know about it without revealing any frivolous details.

“Jim and John look at each other. Throughout the history of their partnership, it’s Jim who takes his cues from his comrade, things as subtle as the tilting of a nostril or the vague tremble in the left knee. Jim is not reading any signals from John, and that’s a first. They’ve never been interrupted before. It’s so embarrassing.”

(Whitehead, Colson. The Intuitionist. London, England: Fleet, 2017, p. 40.)

In this example, we are told how we would normally be shown how Jim and John communicate. Expectations are dashed when they fail to communicate in their usual way and thus the telling phrase “it’s so embarrassing” feels very right.

Comments